Latin America shifts from newborns to elderly care

28-Aug-14, Global Health Intelligence

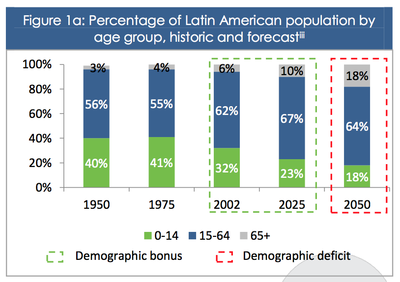

In the 1950s Latin America was characterized for having a relatively high population growth rate of 2.8%i. Urbanization, greater access to education and a larger proportion of women in the workforce lowered population growth to this year’s historic rate of only 1.2%. The expansion and modernization of healthcare access continues to lower mortality rates in Latin America, raising life expectancy levels to near North American rates.

With fewer mouths to feed and more wage earners in the average home, Latin America has recently begun to bask in a 2-to-3 decade demographic sweetspot, much like Japan experienced in the 1970s-90s, the US is now concluding.

Chart: Global Health Intelligence

The demographic dividend lifts household savings and discretionary spending and also expands the tax base, enabling governments to invest in much needed healthcare infrastructure. Latin America is aging and quickly. The fastest household growing demographic is “empty nesters”, Latin seniors who demand more independence and invest more in their health than previous generations of Grandparents.

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) predicts that the elderly (population aged over 65) will rise at a rate three times higher than the growth rate for the population as a whole in 2000-2025 and six times higher in 2025-2050, representing 136 million people by 2050.

Chart: Global Health Intelligence

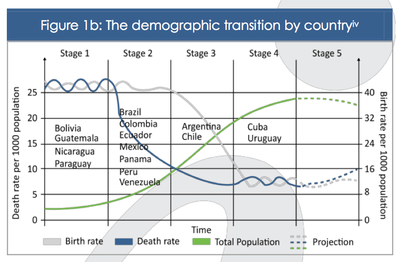

The vast majority of the region’s population is only now commencing its phase of optimal demographics including Brazil, Mexico and Colombia. However, Cuba, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile are further ahead and their experiences can provide some foreshadowing of how the rest of the region will develop.

Socio-economic inequalities and a disconnected rural population are two challenges facing the region’s aging countries. While Latin American poverty levels dropped by half over the past decade, 36% of the region’s population still lives on less than US$ 5.00 per day. v 21% of Latin Americans live in rural areas (and as high as 57% of the population in Caribbean and Central American states). Rising income levels have changed voter priority in maturing countries like Uruguay and Chile from an economic focus to a quality of life perspective. Middle aged Chileans want more government spending on healthcare combined with better access to all. The recent election of President Bachelet’s leftist coalition in Chile was in part fueled by a middle class criticism of the country’s private health sector from hospitals to insurance.

Japan, the U.S. and Europe offer examples of transforming health systems brought on by an aging population. In all three markets, the share of GDP spent on healthcare services and products rose.

In none of these markets was public health infrastructure sufficiently robust to cope with growing demand, so private enterprise stepped in, particularly in non-hospital care such as clinics, ambulatory services, hospice care, nursing facilities, and home care. That opened the market for private healthcare to help pay for the “non-essentials” that the public system could not afford.

Latin America’s fiscal discipline, or lack thereof, is likely to prevent public health from adequately addressing the additional costs of an aging population. That paves the way for massive potential growth in the private sector in fields such as telemedicine, healthcare IT, medical devices and medical technologies that help personalize medicine or improve the efficiency of doctors and nurses.

Drawing upon imported and home grown notions of “healthy old age”, elderly Latin Americans are far more focused today on preventive care and health promotion, than they were only twenty years ago. The market for healthy eating, exercise and diets among the elderly is booming.